A Century Standing Apart

Instantly beloved when it opened in 1921, The Wrigley Building inaugurated the Magnificent Mile in both time and space. Today, we are celebrating the illumination is has provided to both the Magnificent Mile and the City of Chicago for the past 100 years. The Wrigley Building will be boasting numerous centennial celebrations throughout the fourth quarter of 2021. We encourage you to experience The Wrigley Building’s legacy and culture over the past 100 years and explore the activations to celebrate this historical milestone.

The Legacy of The Wrigley Building

A Magnificent Statement

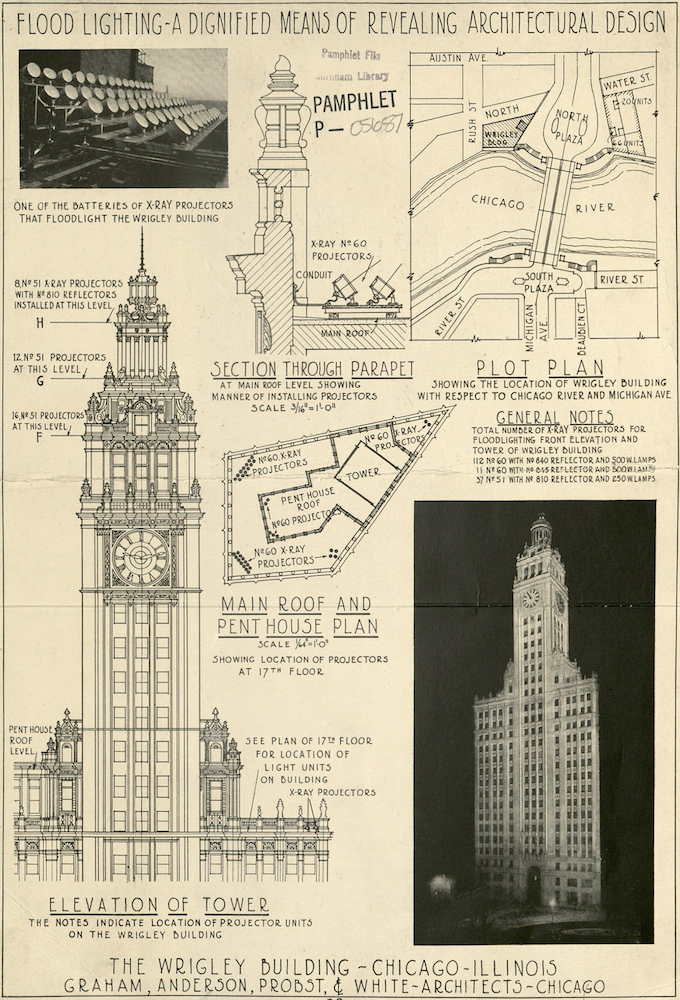

In 1919, William Wrigley Jr. bought an oddly shaped plot of land on Michigan Avenue north of the Chicago River and set to work on the new headquarters for his thriving chewing-gum company. He chose the prolific and pedigreed firm Graham, Anderson, Probst and White as its designers.

At the time, a dense array of industrial structures defined the city’s riverfront. When its south tower opened in 1921, The Wrigley Building’s white terra-cotta and stately profile stood out immediately. Its position at the bend of the river made the building’s facade and impressive clocktower visible for miles around.

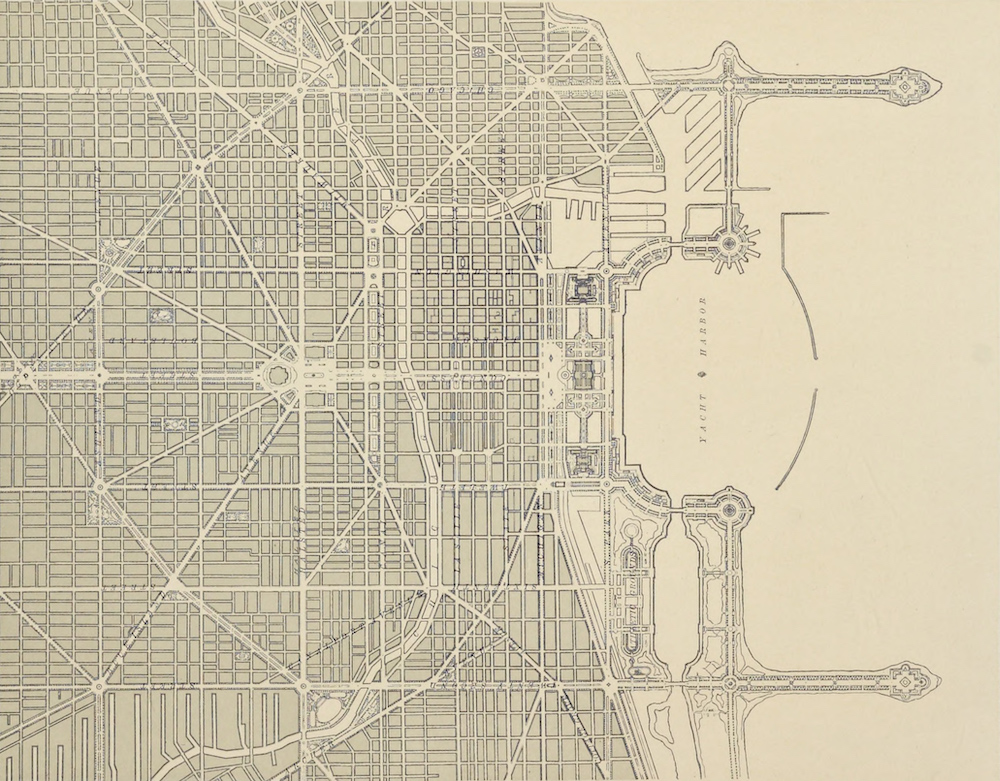

As the first major commercial structure on the newly widened Michigan Avenue, a key aspect of Burnham and Bennett’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, The Wrigley Building embodied a vision of the city’s future.

Architecturally Original

The Wrigley Building is part of the heritage of the famous World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893—nicknamed the “White City” for its bright Beaux-Arts architecture. It combines the neoclassical aesthetics of the fair with the towering steel construction that had already made Chicago a center of commerce when Wrigley arrived in the city to start his business in 1891. (He would introduce Juicy Fruit, one of the company’s best-selling brands, at the Exposition.)

Charles Beersman, the architect who led the design, gave the south building a trapezoidal body that makes the most of its angular site. Above this block he set a massive, 12-story tower, a singular flourish that brought the building to within two feet of the city’s height limit (then 400 feet). The tower’s shape is an explicit reference to the intricately decorated Giralda Tower of the Seville Cathedral, in Spain.

The building is clad in more than 250,000 glazed terra-cotta tiles produced by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company. The tiles come in six shades that shift from warmer to cooler white as they rise, emphasizing the building’s height and setting off the blue of the sky and river. The facade also features terra-cotta molded into in a lively mix of ornamental details borrowing from French Renaissance styling, including mythic figures (cherubs, phoenixes, knights in armor), animals (eagles, lions), natural elements (seashells, vines), and geometric forms. The towers themselves are the best location for viewing some of the richest, most unexpected elements—a hidden treasure for the building’s occupants.

The first tower instantly captivated the city; observers deemed it “magnificent, imposing, unforgettable,” a “Tribute to the Power of Human Jaws.” Wrigley quickly commissioned the second, north tower, which opened in 1924, claiming the even larger annex expressed his “personal faith in the future of Chicago.” The two structures are connected at several points by elevated enclosed walkways, including one stainless steel–covered passage bridging the 14th floors.

Technologically Innovative

Graham, Anderson, Probst and White intended the architecture of The Wrigley Building to be equally striking at night. An extensive and cutting-edge reflector lighting system brought the building national attention during its construction, and the illumination it provides has been a near-constant for 100 years.

“It looks like the city was built just to provide the Wrigley Building with a backdrop.”

— Stephan Benzkofer, Chicago Tribune

The Wrigley Building is credited as the first air-conditioned office building in Chicago. Today, the building’s core and shell have undergone extensive upgrades that have earned The Wrigley Building a LEED Silver designation from the U.S. Green Building Council, among other environmental and energy-use certifications.

Synonymous with Chicago

After it opened, the temple-like cupola on the 26th floor of The Wrigley Building served as a vantage point for viewing the city in 360 degrees as it rapidly expanded. The five-cent admission price included a stick of Wrigley gum. (The Wrigley Building offices still keep Wrigley gum on hand for visitors.)

Since then, The Wrigley Building has become recognizable worldwide not only as a postcard image of Chicago, but also for its place in popular culture and architectural history. Frank Sinatra sang that “Chicago is…The Wrigley Building” in 1965—eight years after giant grasshoppers scaled the structure in the low-rent sci-fi film Beginning of the End. The Art Institute of Chicago holds a fragment of one of the building’s terra-cotta finials in its archives, while the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s collection includes a souvenir coin bank modeled on the building.

A New Chapter

The Wrigley Building begins the next chapter of its story in 2018, under the ownership of Joe Mansueto. Mansueto, who grew up in Northwest Indiana, founded the financial services company Morningstar from his Chicago apartment in 1984. Soon after, he hired the renowned graphic designer Paul Rand to design the Morningstar logo. In 2019, Mansueto became the sole owner of the Chicago Fire, the city’s soccer club, and negotiated the team’s return to play at Soldier Field.

Along with the Belden-Stratford apartment tower in Lincoln Park—another distinctive, historic structure which is soon to be updated with contemporary amenities—The Wrigley Building forms the cornerstone of Mansueto’s real estate holdings. Mansueto’s investment in The Wrigley Building extends his longstanding commitment to exceptional design and to the city of Chicago.